by Audrey Sage

John Parris was born in Sylva, North Carolina and began writing for the local weekly paper, The Jackson County Journal, at the age of thirteen. He later went on to write as a feature writer in New York, then later in London during World War II for the United Press. He continued working in London for the Associated Press as a diplomatic correspondent and was later transferred to New York to cover the United Nations. By 1947 he was ready to return home to the mountains of North Carolina where he continued writing and to later establish his column Roaming the Mountains for the Asheville-Citizen Times.

“For nearly four decades, John Parris’ illuminating non-fiction essays comprised his popular Asheville-Citizen-Times column, “Roaming the Mountains.” When Parris’ columns were first published as books in 1955, they became instant regional classics.

Parris writes with the crispness of Hemingway and the grace of Thomas Wolfe. Indeed, he was a war correspondent like Hemingway and a decorated hero for his work with the Belgian underground during World War II.

But the enduring legacy of John Parris is his work to document the culture and lives of Appalachian people. With every word, Parris links past to present in loving tribute to his Western North Carolina home, its mountains, and its people.” -Two Hoots Press

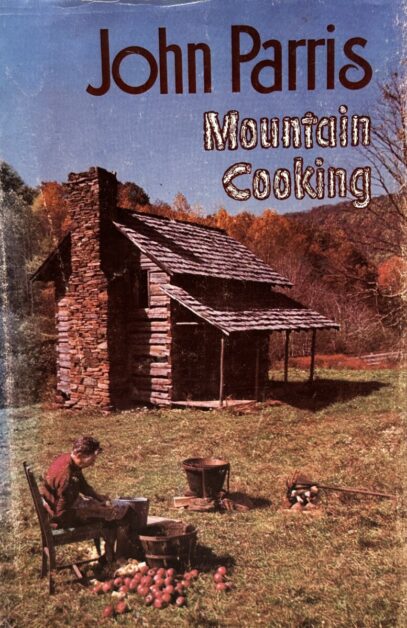

In this volume, Mountain Cooking, published by Asheville-Citizens Times Publishing in 1978, John Parris “reveals the old-time secrets of mountain cooking and makes them possible in every kitchen, but he includes much more: the smell and tase of gritted bread, the aroma of Indian cooking, the challenge of churning by hand, and the lingering whiff of the old wood-burning stove.” In his writing and sharing of tales from the mountains of Western North Carolina, John Parris is able to give to his readers an intimate view of people and ways of living from a region that is close to his heart. His essays through the decades have provided insight and tales of adventure.

We have included two of his essays from Mountain Cooking for your reading pleasure and culinary agenda:

Cat-Head Biscuits and Sawmill Gravy -Murphy, N.C.

They go together like ham and eggs, cornbread and molasses, or mush and milk.

Some folks are so foolish about cat-head biscuits and sawmill gravy that they’ll make a whole meal on them.

“It’s plain and simple fare,” said Aunt Tennie Cloer, “but mighty filling and mighty satisfying. It’ll keep a body from going hungry. A heap of mountain folks made it through the depression of the ’30s on cat-head biscuits and sawmill gravy.”

Aunt Tennie, who was born in 1886 over in the Sugar Fork hills of Macon County, is a right smart woman with a skillet. She isn’t a fancy cook. But she can take simple and inexpensive things and make them pleasure the palate.

“In my time,” she said, “I’ve made many a pan of cat-head biscuits and many a gallon of sawmill gravy. Why, way back yonder, I made ’em for breakfast every morning for six years. That was when I was cooking in the lumber camps.”When you’re cooking for loggers and sawmill workers, it takes a lot to keep’em fed. I cooked regularly for eight men. Part of the time for ten.

No matter what I fed ’em for breakfast – and it was usually fried meat and eggs and biscuits – they had to have sawmill gravy.”That’s what they wanted. And that’s what I give ’em. After they put away their meat and eggs, they’d take a biscuit and break it open and spread it on their plate and spoon sawmill gravy over it. “Sometimes I had to serve it at supper. They’d ask for it.

It didn’t take long to make, you know. I’d make it in the iron skillet after frying the meat and taking it out. “It takes bacon drippings or fried ham grease to make it. What you do is take flour and put it right in the hot grease and let it barely brown, then put in some water to thin it, and add milk and salt and pepper. “It took a half a gallon at a meal to feed them men. That meant using two heaping tablespoons of flour, about a half a pint of water, a pint and a half of milk, and half a teaspoon of salt and the same amount of pepper. “When that cooks, you know, it’ll puff up and make a half a gallon bowl full.”

She paused and shook her head.

“Law, me,” she said, “How them men did like their gravy! They cleaned out the bowl every time. And the biscuits they put away was a sight.

“I baked six pans of biscuits every morning. Had two pans that would hold twelve biscuits each. That meant filling ’em three times and baking ’em in the stove. They weren’t your ordinary biscuits. They were big and thick. And them men never left any. “Made ’em about as thick again as these you buy. They called ’em cat-head biscuits. The only difference between them and regular buttermilk biscuits is in handling the dough.

“For cat-heads, you make up your dough in a big loaf. You don’t roll it out. You grab a hunk of it and squeeze off a piece and pat it out with your hands instead of rolling it out on a board and cutting it with a biscuit-cutter.

“Big biscuits they are. Big as a cat’s head. That’s the way folks liked ’em back then. It’s the way my mother always made them, and I learned from her when I was just a little thing big enough to stand up to the kitchen table and mix the dough. “My mother usually rolled out her dough and cut out her biscuits. She used the top of a baking powder can for a biscuit-cutter. But when she was in a hurry, she’d just knead her dough into a loaf and choke off her biscuits and pat ’em up and put ’em in the pan and bake ’em.

“That’s what I done when I was cooking in the lumber camps. When you’ve got a big bunch of men waiting for breakfast and having to be at work on time and it takes a lot of biscuits, you’ve got to be quick. So you squeeze ’em or choke ’em off instead of rolling out the dough and cutting ’em out. “Them men had to have biscuits twice a day. Breakfast and supper. I fixed cornbread for dinner, and had both cornbread and biscuits for supper. It didn’t take as many biscuits at supper unless I fixed sawmill gravy when they asked me to. “Another thing I’d fix for ’em was cornmeal mush. Now and then they’d tell me that’s what they wanted for supper. Just mush and milk, and nothing more.

“Now, to make mush for eight men come in from working all day took something, I’m telling you. It had to be made in a gallon pot. “I’d get my water boiling in that pot, put in some salt, sift my cornmeal, and then stir in the meal a little at a time and stir it while it was boiling. Let it cook until it was done. Stirring to keep it from sticking. It got so thick that you could might near cut it with a knife. Didn’t take but about fifteen minutes.

“I’d take it to the table in two big bowls and the men would take it and dip out a big spoon full and put it in their glass of sweet milk. They ate it out of the glass with a spoon. They kept right at it until they needed another glass of milk and then they went through more mush and more milk.

“That’s all they wanted for supper. All they wanted – just mush and milk. Folks back then used to eat a lot of mush and milk. You hardly ever hear of it anymore. But sometimes I fix it for myself. Just as I still make a meal every now and then on cat-head biscuits and saw mill gravy.”

Aunt Tennie isn’t the only one who still fixes biscuits and sawmill gravy. And it isn’t only out in the country that sawmill gravy is served up. As a matter of fact, it is often to be had in some of the public eating places in the mountains that specialize in mountain dishes. It’s a fixture on the breakfast menu at Phillips Restaurant over in Robbinsville. And it always turns up on the luncheon menu when there’s creamed potatoes. “We’ve been serving it regularly for breakfast since we opened our restaurant 20 years ago,” Mrs. Patton Phillips, another smart lady with a skillet, told me one day last week while Smith Howell, the banker, and I stirred up old memories with a lavish of her sawmill gravy. “Folks around here in the old days,” she said, “used to call it ‘Life Everlasting’, because, they said, it had saved so many people’s lives. It was just about all they had to eat. They made a meal on it and biscuits.”

She paused a moment, looked at our plates of gravy, then laughed. “You know.” she said, “I’d eat it every day if it didn’t make me so fat.”

Poke Sallet – Dodgin Creek

Poke Sallet is a favorite dish of mountain folks whose tastes run to natural foods.

whose tastes run to natural foods. Of all the wild greens, it’s the best known and the most sought after.

But, like collard greens and hominy grits, a taste for poke sallet must be cultivated by outsiders.

Mountain women begin picking poke as soon as the young sprouts shoot out of the ground in the spring, and they keep right on picking it and serving it until the sprouts grow old and tough.

Some of them, like Mrs. Elvie Corn who lives here on Dodgin Creek in the hills above Cullowhee, have been picking poke since they were kneehigh to a duck. Mrs. Corn has been searching it out and picking it for more than 50 years.

“Poke is best,” she said a couple of days ago,”when the sprouts are white and tender with just a little tuft of green leaves at the top. But you’ve got to pick it with a sparing hand. The root is a deadly poison. And if you get too much of the lower part of the shoot it’ll give a body a fit when they eat it.”

She had just come in from picking a mess of poke sallet from the field back of her house.

“There’s different ways of fixing poke,” she said. “I’ve never seen any written recipes for it. I learned how to fix it from my mother and my grandmother. But all of it has got to be cooked.

“First, you’ve got to parboil it. I boil mine three times. That get’s out any poison there might be. With the first boiling, the water turns red. You pour that off, put in fresh water and boil it again. And then you pour that off, put in water again and boil it a third time. “You can serve the sallet as it comes out of the pot. Eat it with vinegar poured over it. But the way I like it best is to take it when it comes out of the pot, cut it up, put it in a greased frying pan with eggs and stir it all together.

“Another way to fix poke is to take it after you’ve parboiled it and cut it up and roll it in corn meal and fry it like you would okra. It’s mighty tasty, too, if you’ll chop it up with onions and fry it with bacon or fat-back drippings.”

I told her that my wife cooks poke like asparagus and serves it with hot Hollandaise sauce.

Mrs. Corn recalled that as a child all the old folks warned her to be mighty particular about picking poke too close to the root. “They said if you ate the root it would kill you. But my grandmother used to get the roots and boil them until they were tender and then sprinkle cornmeal on them and put them out for the chickens to peck on. She claimed it was good for them.”

While poke sallet is her favorite greens, Mrs. Corn also has a taste for crow’s-foot, speckled dock, lamb’s-quarters, and branch lettuce – all of which were in the diet of settlers during the early days of this country.

“Some folks,” she said, “call crow’s-foot Indian mustard. But all the old folks referred to it as crow’s-foot. If you’ll examine the leaves, you’ll see they look like crow’s feet. Now, the way to prepare crow’s-foot is to take the tender leaves and scald them with hot grease, like you would with lettuce that comes out of the garden, and then pour vinegar over them.”

“But you’ve got to cook lamb’s-quarters and speckled dock, just like you fix poke sallet. I’ve heard some folks call lamb’s-quarters wild spinach. Grandma parboiled her speckled dock and then fried it in grease.

“Now, as for branch lettuce, it’s mighty good but it’s hard to come by. Not like poke. Grows only in the winding hollows where the water comes warm from the earth, or in and near the edge of a branch where the soil is dark and damp. You won’t find it on just any stream. The way I fix mine is to chop it up coarsely or take only the smallest leaves and spread it on a serving dish. I make a sauce of hot vinegar with a touch of sugar and bacon or ham drippings and pour over it. Then I cover it with sliced boiled eggs.”

At our house, I told Mrs. Corn, we never chop up the leaves, no matter the size, and then told her about the dressing my wife concocted for branch lettuce. Dorothy takes a couple of rashers of bacon and fries them crisp. She takes the bacon out of the pan, leaving the drippings, and cuts up the bacon. Then she puts into the frying pan about one-third cup of vinegar, a quarter cup of water, two teaspoons of sugar, a half teaspoon of salt, then brings the mixture to a boil. A moment later, Dorothy takes thinly sliced onions and the diced bacon and puts them in with the lettuce. And over the lettuce she pours the mixture, then tosses the branch lettuce until it is all mixed up.

“That sounds real good,” Mrs. Corn said. “I’ll have to find me some branch lettuce and try it. Let me get a pencil and some paper and put down that recipe.”

When she finished, she sat a moment longer without saying anything.

“You know.” she said finally, “I spent a lot of time with my grandmother when I was growing up. She taught me a heap of things. She taught me to tell all the wild greens and wild fruits.

Back then folks depended on them more than they do now.

“I’d go out with her into the fields and the woods and she’d show me the things a body could eat and things a body couldn’t.”

She paused and a smile crept across her face.

“My grandmother was a good teacher,” she said. “I’ve never forgot what she taught me about poke and the other wild greens. And I’ve been picking them spring in and spring out since she first showed them to me.”