by Audrey Sage

As the Special Collections and University Archives continues in its efforts to develop, preserve and build their collections, I appreciate the immense responsibility it is to become a caretaker of these artifacts, these pieces of history that takes shape in so many different forms. If it were not for the caretakers of time and information, so much would be lost, both in the telling and of the physical items.

Special Collections recently received a large number of items from Dr. James B. Gutsell, B.S., M.A., Ph.D.; Guilford College, Professor of English; 1963 – 1999. Among these gifts are several works that were preserved and carefully maintained by his mother over a long period of time. Her care and foresight to preserve these interesting, fragile and unique pieces becomes a treasure trove for those of us now, who are able to handle and appreciate these wonderful volumes.

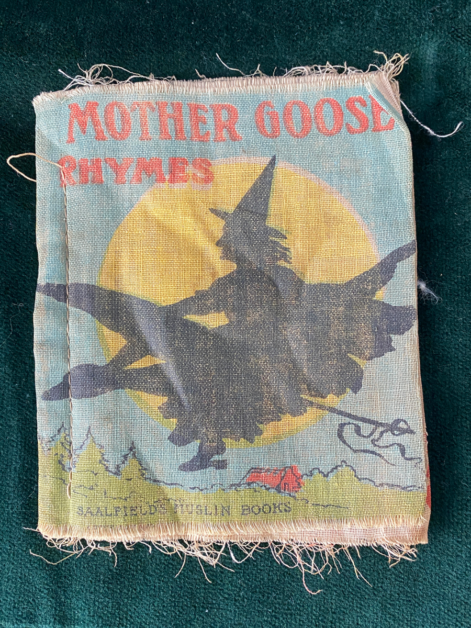

Among Dr. Gutsell’s donations is a Saalfield Muslin Book of Mother Goose Rhymes. This volume was most likely printed in the earlier part of the 20th century. The Saalfield Publishing Company published books and other products from 1900 to 1977, and was once one of the largest publishing companies in the world. These cloth books were attractive as being washable and durable books for children.

As stated in the Encyclopedia Britannica,” “Mother Goose” was first associated with nursery rhymes in an early collection of “the most celebrated Songs and Lullabies of old British nurses,” Mother Goose’s Melody; or Sonnets for the Cradle (1781), published by the successors of one of the first publishers of children’s books, John Newbery. The oldest extant copy dates from 1791, but it is thought that an edition appeared, or was planned, as early as 1765, and it is likely that it was edited by Oliver Goldsmith, who may also have composed some of the verses. The Newbery firm seems to have derived the name “Mother Goose” from the title of Charles Perrault’s fairy tales, Contes de ma mère l’oye (1697; “Tales of Mother Goose”), a French folk expression roughly equivalent to “old wives’ tales.” “

Often the Mother Goose stories are often attributed to a Mary Goose, a woman believed by some to be an author of countless cherished nursery rhymes, where in Boston Massachusetts, there is a tombstone of a Mary Goose buried in 1690, where visitors toss coins for good luck, but it is undoubtedly believed she is not the original Mother Goose. There is also another local legend of the widow of Isaac Goose, Elizabeth Foster Goose being the Mother Goose, who often entertained her grandchildren and local children with songs and rhymes. Most historians agree that neither of these women are the originators of the Mother Goose stories but rather the name “Mother Goose” evolved over a longer period of time. According to the research by Laura Schumm, “the name may have originated as early as the 8th century with Bertrada II of Laon (mother of Charlemagne, the first emperor of the Holy Roman Empire) who was a patroness of children known as “Goose-foot Bertha” or “Queen Goosefoot” due to a malformation of her foot.”

“By the mid-17th century, “mere l’oye” or “mere oye” (Mother Goose) was a phrase commonly used in France to describe a woman who captivated children with delightful tales. In 1697, Charles Perrault published a collection of folktales with the subtitle “Contes de ma mère l’oye” (Tales from my Mother Goose), which became beloved throughout France and was translated into English in 1729. And in England, circa 1765, John Newbery published the wildly popular “Mother Goose’s Melody, or, Sonnets for the Cradle,” which indelibly shifted the association of Mother Goose from folktales to nursery rhymes and children’s poetry, and which influenced nearly every subsequent Mother Goose publication.”

We are grateful to add this historical piece to our collections, becoming the next in line to care for this volume.

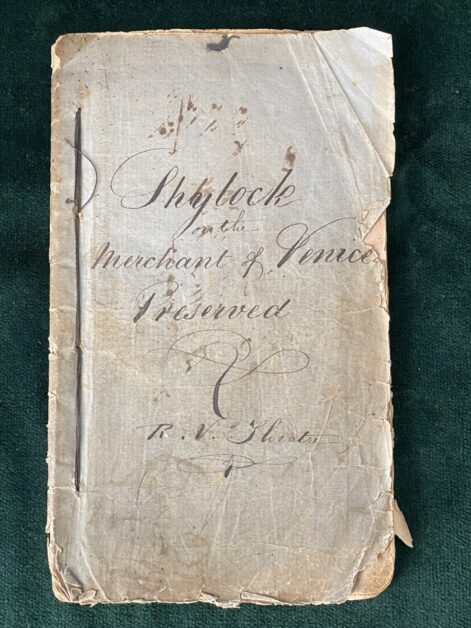

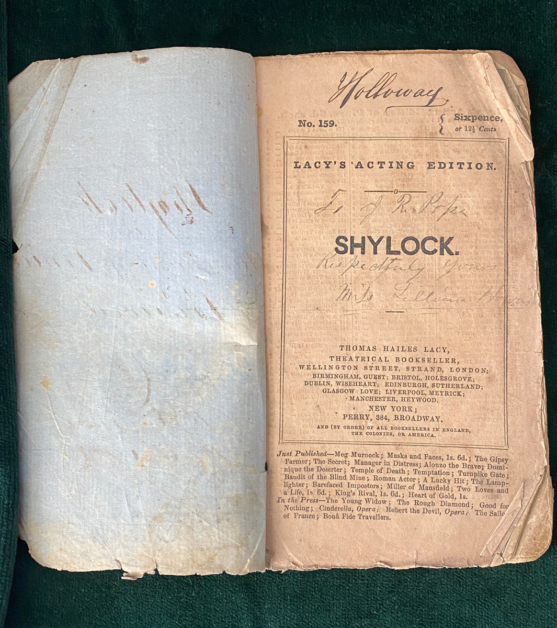

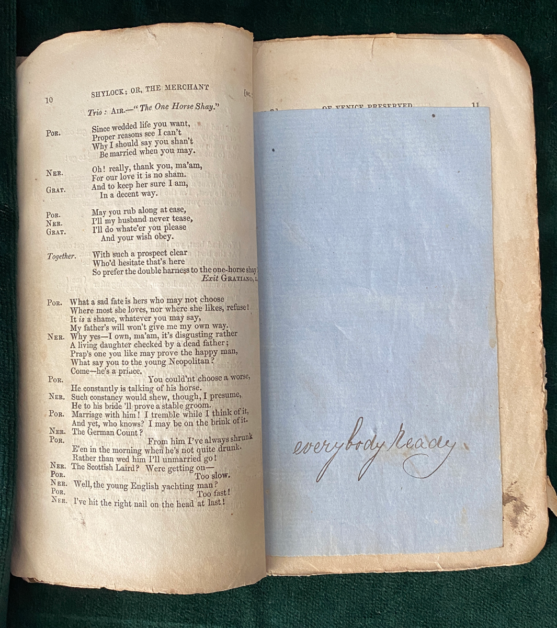

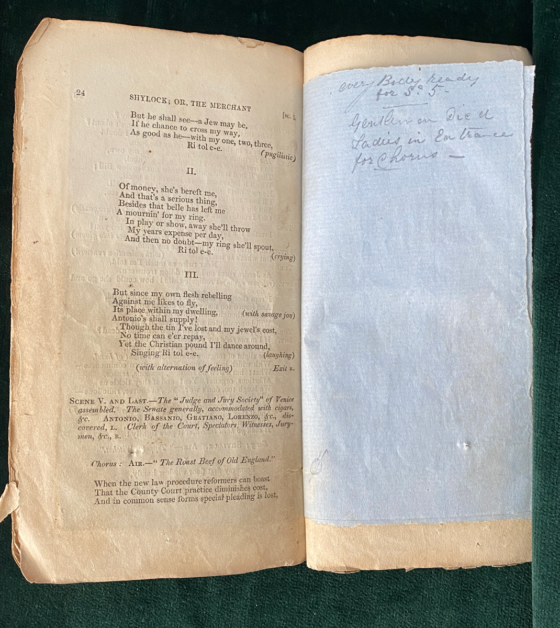

Another wonderful and visually evident historical volume from Dr. Gutsell is a well used and preserved actor’s copy of “Shylock” or “The Merchant of Venice” by William Shakespeare. It was published in 1853 by Thomas Hailes Lacy, Theatrical Bookseller, based in London and New York, called “Lacy’s Acting Edition, and sold for sixpence.

This is so worn, contains some incredible notes within its pages, and really expresses , to me, the journey this little volume has taken. It is a paper covered volume that is sewn simply through the side with a limited amount of thread which has held up amazingly well through the last century.

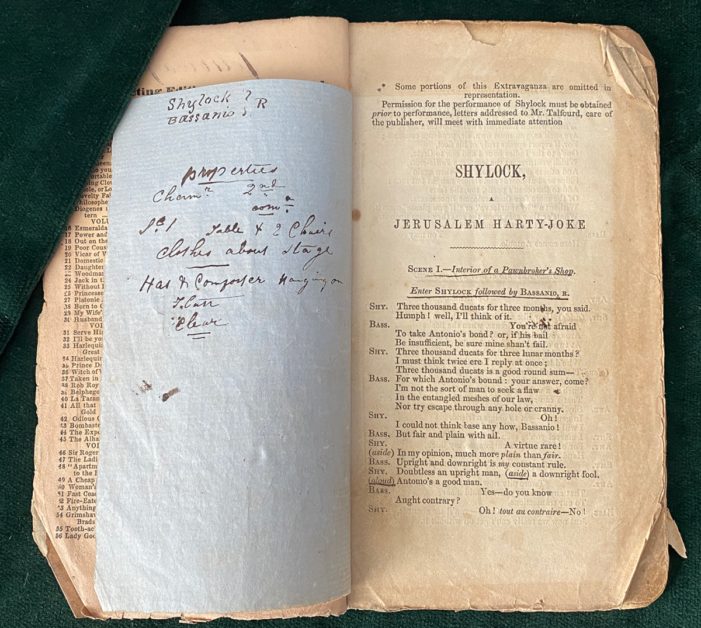

It is very interesting to note the blue blank pages sewn into the copy specifically for directional notations and actor’s personal cues to aid them while performing. I always like to realize the dirt particles and other elements that are caught within the pages could have been trapped there a hundred or so years ago. It would be enlightening to have these analyzed to discover from where and when these particles came.

It is amazing to consider how many hands have held this book, how many actors who have studied these lines of Shakespeare, how many performances have been viewed based on these words. Publishers who have printed endless editions are the caretakers of history through the continuation and documentation of the words and artistic integrity of great writers around the world. Shakespeare was a documentarian of his time by penning his thoughts, observations, political and social commentaries through his creative writing, which reflected his view of the world in which he lived.

Being able to care for this little volume, and to read the penned notes on the page from some unknown director or actor, “Everybody ready”, brings me a sense of familiarity to that person of the past, in the smallest way, and the desire to take extra time and sensitivity for the preservation and handling of this historic artifact for those who may pick it up and contemplate its richness, in the future.

Everybody ready.