By Shelbi Webb

Institutions of higher learning not only offer opportunities for academic knowledge, but also philosophical and cultural understanding. The “foreign exchange student” has long served as a pathway for experiencing the world. However, cultural exchange can be implicitly biased. Yoko Ishikawa, a Japanese exchange student at Woman’s College or “W.C.” (now UNCG) in the 1950s, shared her culture with fellow students, though she was seen through a western lens. How does true cultural exchange take place with tinted lenses? As an international traveler, Yoko studied in her birth place, Yokohama, as well as New York City, London, Tokyo, and Greensboro. Yoko received a Fulbright scholarship according to an article in the Summer 1952 issue of the Alumnae Magazine:

“In the noonday mail last June, a letter postmarked Japanese Ministry of Education came to the Ishikawa home in Tokyo, and, opening it, Yoko learned that through the U.S. Department of State, Fulbright Scholarships, and the Service League of the Woman’s College of U.N.C. Greensboro, she was going to America to study for a year.“

The magazine shares details of Ishikawa’s life. Born in 1930, Yoko mostly lived in Japan, but her late father’s job at Mitsubishi led her to New York City and then London. After four years, a year before Pearl Harbor in 1941, the Ishikawas moved to Japan where they remained throughout World War II.

A 1952 W.C. Alumnae Magazine article describes a harrowing experience of Yoko’s when she was 13, a bombing of Tsuru’s Girls High School in which twenty students died.

Of the six articles that document Ishikawa’s time at W.C., only one sentence speaks of students talking to Yoko about World War II. Instead, most of the article focused upon Japanese customs such as betrothals.

That November, in the student newspaper The Carolinian the “Whistlestop” columnist writer proclaimed, “I wish to extend congratulations to Yoko Ishikawa, who gave us such a wonderful talk in chapel on Tuesday. I would also like to express my sincerest wish that Yoko will enjoy this year at W. C. and learn as much from us in nine months as she taught us in that ten minutes in Aycock” (Nov. 14, 1952, p. 4). Indeed, Yoko fulfilled this instructional role. She shared Japanese customs by holding a tea ceremony in the Shaw Dormitory in December and comparing Japanese celebrations to Western ones (The Carolinian, Dec. 19, 1952).

The “foreign exchange student” tradition we see in the United States educational sphere sets the stage for learning a new culture. From another perspective, the tradition also underpins the standard for minorities having to “represent” in a burdensome way that leads to reinforcement of stereotypes. Although the articles convey Ishikawa’s experience as more of the former than the latter, they also reveal the constraints of that exchange stemming from racial bias namely the exoticization of Asians and Asian women.

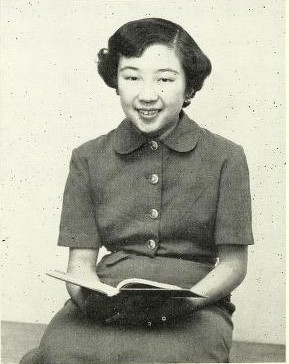

In The Carolinian Ishikawa describes her cheeriness as looking at an “oriental sun” (Sept. 26, 1952, p. 3). Using terms related to the “orient” is a homogenization of the vastly diverse Asian cultures and types Asians as a racial “other.” The article also includes a description of “small” Ishikawa’s “shy” way of gathering information about United States culture from her classmates (Alumnae Magazine, Summer 1952). These kinds of descriptions, though innocuous and true to an extent, help to reinforce stereotypes of Asian women being delicate dolls and “Lotus Blossoms” (see Kuo article) and highlight one of Yoko’s characteristics at the expense of others. Moreover, the focus on the betrothal customs highlights cultural aspects sometimes misconstrued as depicting East Asian women as passive and submissive. Considering these articles were published in the 1950’s, the racial and gendered stereotypes seem normal. However, considering Ishikawa’s ability to endure a war in which the United States bombed her school and killed 20 of her classmates, Yoko shows a deep strength that counters normalized bias.

“Chance Second Meetings,” an article in the April 24,1953 issue of The Carolinian, revealed more dimensions of Ishikawa yet the author is still hedged in bias. Yoko is reacquainted with Dr. Maude Williamson, a visiting professor of home economics. Dr. Williamson recognized Yoko from her performance in As You Like It while at Tsudo in 1951. The article noted that Professor Williamson “carried with her the special memory of the young Japanese girl who portrayed the Shakespearean character in such perfect English” (p. 1). Associating Ishikawa’s success of her performance to her English speaking, rather than her acting, emphasized the Asian stereotypical descriptions of Asian accents, or “broken” English.

The November 21,1952 issue’s “Ink On My Hands” gave Ishikawa a chance to write about her experiences in her own words. As a guest columnist, Yoko wrote about what she’d be doing if she were in college in Japan: She noted the lack of roll call, because students want their money’s worth of education which instilled in them accountability and motivation to attend classes. She spoke about excursions to concerts and shows. She wrote of her love of literacy, and her enjoyment of book collecting and bargain hunting, including the challenge of obtaining the hard-to-find foreign books.

She continued to describe the multifaceted nature of her life:

“What am I doing at W.C. right now? Why, of course, trying to figure out what is so screaming funny about Pogo, and how people manage to get their work done while having so many dates.” (p. 2)

Yoko Ishikawa attended UNCG as an English major taking child psychology classes, so when she became a teacher, the knowledge would bolster her abilities. During that time, she also built ties to the people at UNCG. In fact, an article in the October 9, 1964 issue about links between Tokyo and Greensboro revealed that “Yoko and her friends rolled out the red carpet” for UNCG’s Drama department when, on a tour to different U.S. Army and Naval bases, they visited Tokyo (The Carolinian, p. 3). The effort to form such bonds cannot be accurately understood without acknowledging the cultural and gendered context. This includes the imbalance of power between Ishikawa – a person of color – and the all-white student body of UNCG, for the university was not racially integrated until 1956.

This interpretation of events applies today’s understanding of predominantly white spaces causing people of color to employ methods of protection against varying degrees of discrimination. This includes emulating whiteness in the belief that closeness to whiteness serves as protection (Kumar) along with strategically silencing oneself to avoid conflict with dominating forces of White biases (Matthews, 80). Although Ishikawa’s words and actions as revealed in the newspaper clippings do not explicitly model these forms of protections, they reflect their essence once the reality of anti-Japanese racism in post-WWII USA is acknowledged. Moreover, international relations upheld Western ideals in a way that perpetuated whiteness (Zvobgo), which granted White travelers a red carpet in non-white nations in many cases. The subtle forms of racism Ishikawa faced, like exoticism, count as situations in which Ishikawa would need to navigate a hegemonic culture as a minority, which required her to avoid conflict by not challenging the biases of her White peers.

Though warm and friendly experiences is one side to Ishikawa’s foreign exchange student story, failing to acknowledge the gender and racial inequalities forming her reality would not be telling the whole story. Likewise, failing to mention my position as a woman of color (WOC) interpreting Ishikawa’s story through the lens of my own marginalized backward would be a remission. However, the realities women of color face today, such as those outlined by Kumar and Matthews, apply to WOC’s of the past, granted to different extents according to individual circumstances. For example, Ishikawa’s status as a foreign person means Zvobgo’s point likely factored into Kumar and Matthews concepts of conforming to Whiteness as a means of social protection as she traversed predominantly white spaces, especially during post-WWII time during which a rebuilding and westernizing Japan joined the United Nations. Upholding western – as in White – standards occur at the macro level and affect relations on the micro level.

Despite the honest exchange of experiences, distortion of character due to the biases established by hegemonic forces can prevent true relating and understanding. However, the growth of awareness and active resistance against such biases in the following years enabled the ability to truly see color.

Student organizations, like YUVA and the Asian Student Association, frequently offer us such opportunities:

Ultimately, connection is the purpose of cultural exchange. We are all part of this world, so we too understand different cultures on the micro-macro, personal and general levels. We cannot do that through tinting our lenses and distorting our vision. Though, as we have seen in recent years through mass shootings and Asian hate crimes, racism is still alive and well, but truth and justice are just as everlasting — and stem from a stronger substratum. Continuing to use voices, reach out, and connect, whether through writing an article or artistically imitating life, keeps implicit bias from completely controlling our conscious minds. No one, especially those from marginalized communities, needs to carry a cultural educator card. Assuming the purpose of minority presence is to teach, carries its own unconscious bias. The people actively choosing to share their experiences and insight certainly offer a chance to tear down such biases. Exchange is not a smooth, flawless process, instead it always demands awareness, diligence, and time.