by Audrey Sage

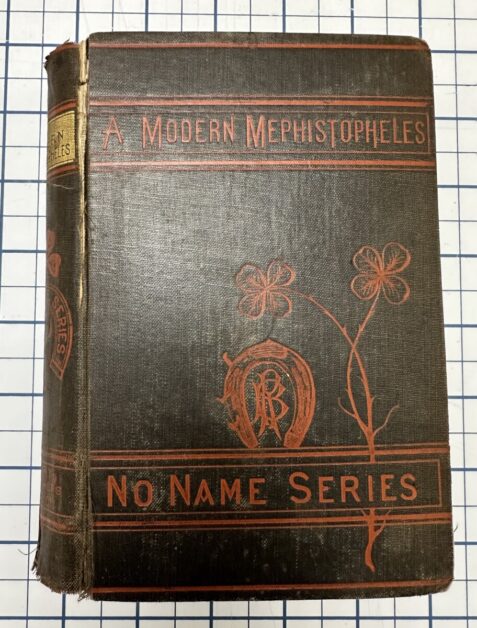

A Modern Mephistopheles was written by Louisa May Alcott and published anonymously in 1877, when she was 25 years old, perhaps so she could explore a “darker side” without tainting her reputation. It was published under her name in 1889, along with her similarly dark story, A Whisper in the Dark. A mephistopheles is a demon from German folklore. A journal entry from February, 1877 explained what inspired her to write it: “It has been simmering ever since I read Faust last year.”

This chilling tale of lust, deception, and greed begins on a midwinter night as Felix Canaris, a despairing writer about to take his own life, is saved by a knock at the door. His mysterious visitor, Jasper Helwyze, promises the poor student fame and fortune in return for his complete devotion. The embittered Helwyze then plots to corrupt his overly ambitious protégé by artfully manipulating the innocent and beautiful Gladys. When Helwyze decides that he wants Gladys for himself, Felix must defend the adoring young woman from the corrosive influence of his diabolical patron. A novel of psychological complexity that touches on controversial subjects such as sexuality and drug use, A Modern Mephistopheles is a penetrating and powerful study of human evil and its appalling consequences.

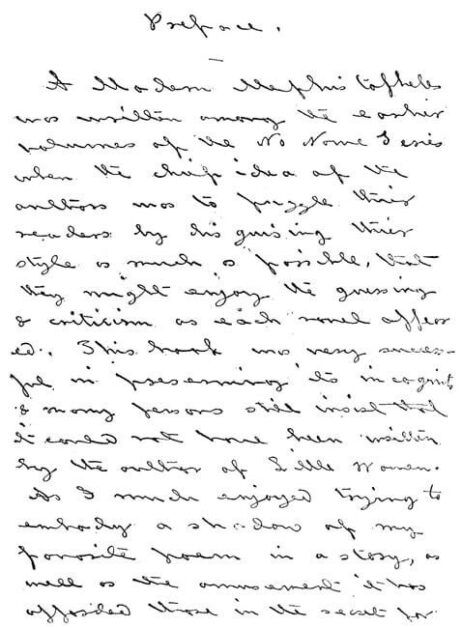

From Alcott’s penned preface, 1889:

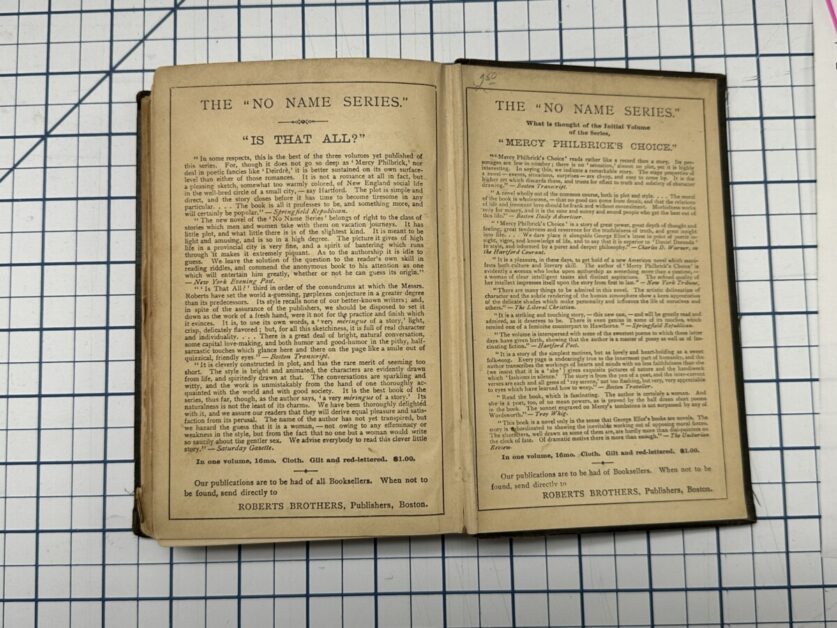

“A Modern Mephistopheles” was written among the earlier volumes of the No Name Series, when the chief idea of the authors was to puzzle their readers by disguising their style as much as possible, that they might enjoy the guessing and criticism as each novel appeared. This book was very successful in preserving its incognito; and many persons still insist that it could not have been written by the author of “Little Women.” As I much enjoyed trying to embody a shadow of my favorite poem in a story, as well as the amusement it has afforded those in the secret for some years, it is considered well to add this volume to the few romances which are offered, not as finished work by any means, but merely attempts at something graver than magazine stories or juvenile literature.”

“A daughter of the transcendentalist Bronson Alcott, Louisa spent most of her life in Boston and Concord, Massachusetts, where she grew up in the company of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Theodore Parker, and Henry David Thoreau. Her education was largely under the direction of her father, for a time at his innovative Temple School in Boston and, later, at home. Alcott realized early that her father was too impractical to provide for his wife and four daughters; after the failure of Fruitlands, a utopian community that he had founded, Louisa Alcott’s lifelong concern for the welfare of her family began. She taught briefly, worked as a domestic, and finally began to write.

Alcott’s stories began to appear in The Atlantic Monthly (later The Atlantic), and, because family needs were pressing, she wrote the autobiographical Little Women (1868–69), which was an immediate success. Based on her recollections of her own childhood, Little Women describes the domestic adventures of a New England family of modest means but optimistic outlook. The book traces the differing personalities and fortunes of four sisters (Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy March) as they emerge from childhood and encounter the vicissitudes of employment, society, and marriage. Little Women created a realistic but wholesome picture of family life with which younger readers could easily identify. Alcott’s books for younger readers have remained steadfastly popular, and the republication of some of her lesser-known works late in the 20th century aroused renewed critical interest in her adult fiction.” -Encyclopaedia Britannica by Amy Tikkanen.

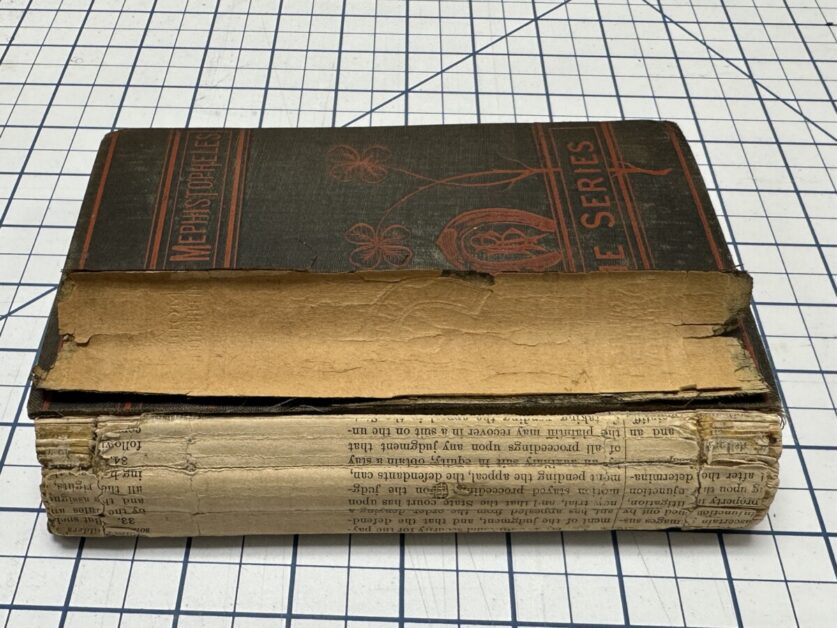

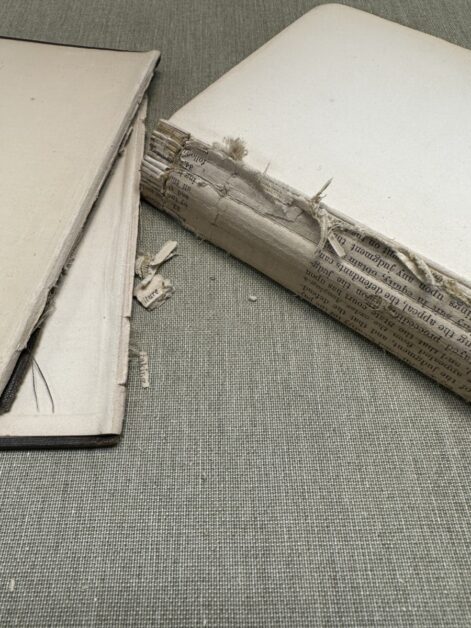

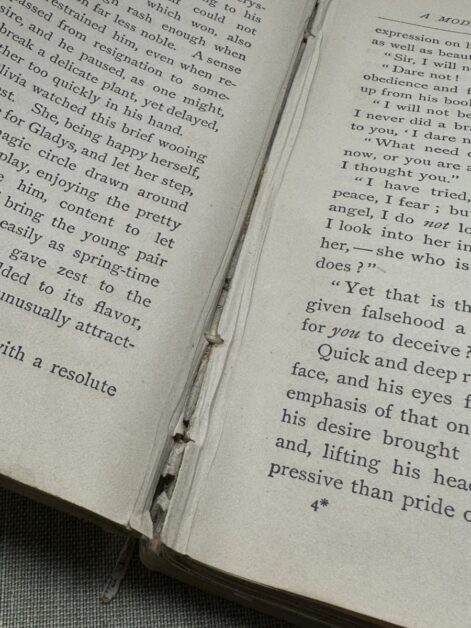

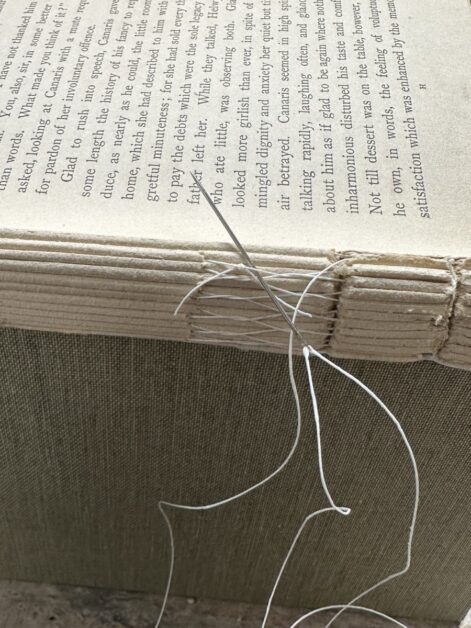

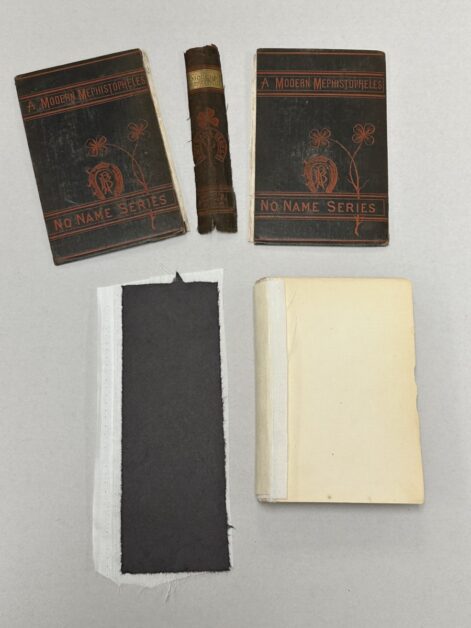

This volume, published in the No Name Series in 1877, had become worn, the spine cover cloth hanging by threads, and the spine and sewing materials were deteriorating.

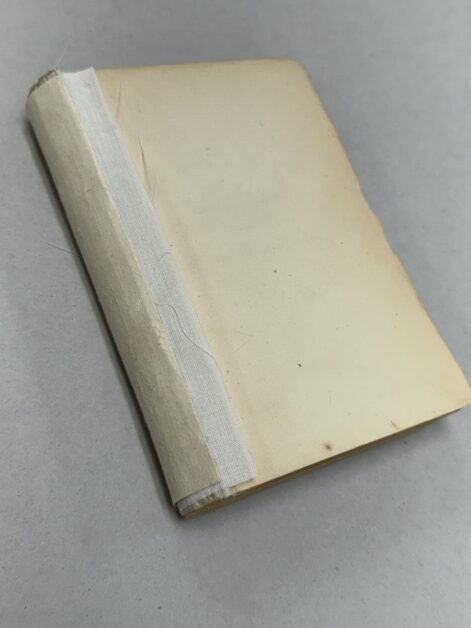

toned Japanese papers and linen cloth.

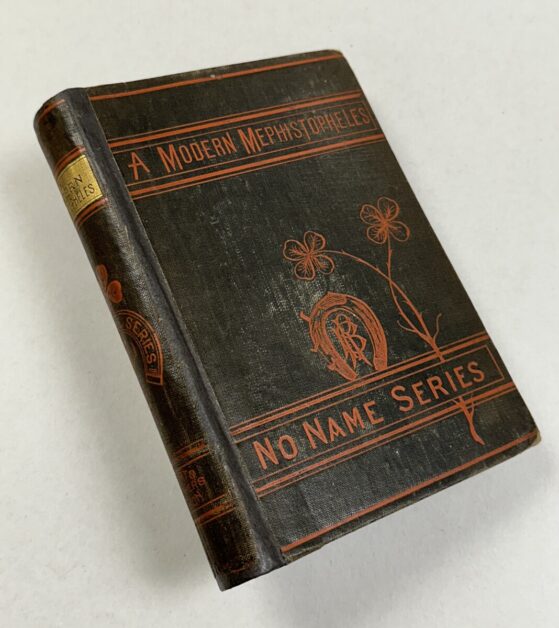

The newly restored volume of A Modern Mephistopheles is now ready for the next century.