By Katherine Widner

*Katherine Widner was a UNC Greensboro Library and Information Science Student who wrote this article in conjunction with her final Capstone Project, the North Carolina Cookbook Storymap.

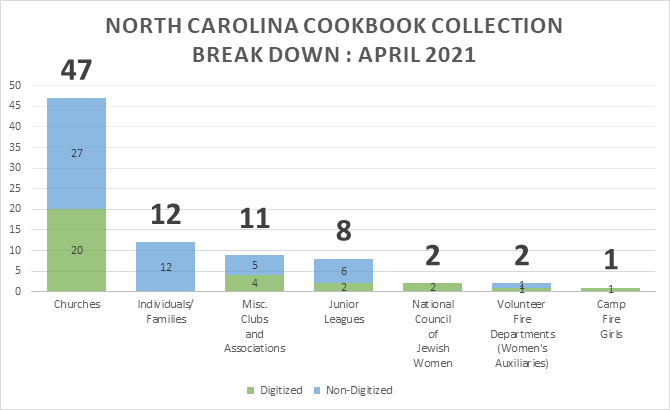

In my work with the NC Cookbook Collection of the Martha Blakeney Hodges Special Collections and University Archives here at UNC Greensboro, I’ve come to learn a lot about traditional southern ideas and ideals. Though the cookbook collection has a wide variety of cookbooks all created with different purposes in mind and all coming from different entities over the last 80 or so years, there was one particular thing about this collection that caught my attention immediately when I began my work. Currently, there are 80 books in the collection that have been cataloged, 30 of those have been digitized and, of course, the collection is ever-expanding. But in mapping the basic data of these books, it becomes obvious that a huge majority of the collection, currently, is church cookbooks.

When I realized that so many of the books were created and disseminated by churches and church communities, I was intrigued. I found myself wondering why there were so many church cookbooks, and what all these books have to say about our ideas surrounding church itself—be it religion, faith, or just the idea of fellowship in general. The more I explored these texts, the more I recognized that it is in the shared similarities and the distinct differences between each book’s stories and histories that the truth rests.

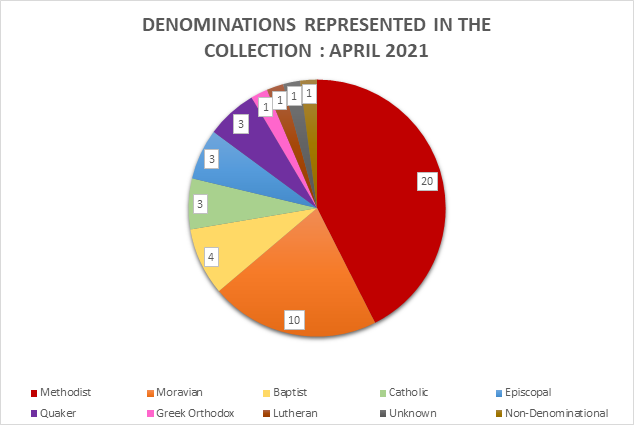

Before I delve into my findings and thoughts, I do think it is important to also note that this collection is a work-in-progress (as all collections are, really). Though I will state my thoughts about the books I worked with this semester, I think it’s important to remember that this is not the entirety of the collection at all. Though all of the religions in the books in the collection right now are Christian or Christ-centric religions, that doesn’t mean that there aren’t other religions yet to be cataloged or digitized. I also think it’s important to note the variety of denominations within the spectrum of Christianity that are currently represented in the collection because it not only gives us an idea of denominational trends in cookbooks over the years, but it also gives us a rough sketch of the history of our state. Additionally, in the creation of this StoryMap project, we can further map denominational clusters in different regions of North Carolina, as well as work to highlight trends or denominations that may be often overlooked or purposefully ignored. These are all prospective ideas for the future, however, so for the time being I will focus on my work with the present collection.

As previously mentioned, the books in the collection currently are Christian or Christ-centric religions. This is particularly interesting because the Bible of Christian tradition is centered, believe it or not, all around food. From the forbidden fruit in Genesis to the Marriage Supper of the Lamb in Revelation, with every story and parable one can find faith, food, and fellowship. Food in the Christian tradition, be it metaphorical or literal, has a rich history that has been documented and practiced by many. The very person the whole religion is centered around, Jesus Christ, was (according to different testimonies) a man who liked food and partook in meals and feasts quite often, even using food to teach his people ideas surrounding religion. In fact, throughout his life, food was an important part of his teachings. He celebrated Passover and the Lenten season, he often fasted, and he prayed and thanked God before his meals. He provided food for over 5,000 people from only five loaves and two fish, and he also turned water to wine. He often used food in his stories to help relate his message to his followers, as can be evidenced in the parables of the cursed fig tree and the leaven, to name only a few. He is said to have shared meals with people seen as social pariahs, such as tax collectors, uninvited guests, and people who thought themselves (and were often viewed by others) as small and unworthy. Before his death, which he knew was coming, he sat with his disciples and had a feast (the “last supper”) where he told people that his body was bread, and his blood was wine—that he was the lamb of God, sent to be sacrificed to save the world. Even after his death and resurrection, he revealed himself as a stranger to some of his disciples on the road, and it was only when they sat down to eat a meal together that they realized, through how he spoke and broke his bread, that he was Jesus. Through everything Jesus did, and throughout the history of Christianity, one can always find food. The question remains, however, why? What is it about food that is so important to religion and, more specifically, Christianity?

Though there are truly no correct answers to these questions, I feel like the cookbooks in our collection help to shed light on the mystery. In these cookbooks you don’t typically find recipes entrenched in the Christian tradition (like Jesus’ homemade apple pie recipe, for instance). Instead, you find a hodgepodge of hand-me-downs—a patchwork quilt made of the lives of normal people. Though the people behind these books practice Christianity today in modern churches, their version of Christianity is not the same as it has always been, and in examining these cookbooks we are able to see snapshots of our history, not as one people united under one religion, but instead as just people, united by the fact that we all love and need food.

So, what do these books have to tell us? At the surface level, it’s easy to assume these church cookbooks are just relics of the past and nothing else, but in examining how they are constructed, the purpose and message of these books becomes more and more evident. Though these books are all from different churches, some of them share the same formulas and layouts (in fact, some even share the same recipes because they used the same publishers). The formula is pretty straightforward: typically, these books start with their cover page, either with a photograph of the church or an illustration of something, and on the pages before the index of recipes (if there is an index—and sometimes, there is not) they usually have the people responsible for the making of the cookbook and/or recipes (such as cookbook committees, youth groups, Sunday school classes, etc.). A lot of times you’ll also find a note from the person in charge such as a pastor or priest, usually with a brief summary of the church’s history, as well as a dedication page to someone important or perhaps even deceased. It’s also very common to see the church’s creed or mission listed and printed (for some reason, there was a trend where the mission was printed on what seems to be a clipart scroll or sheet of paper). There are also, of course, pages with simple prayers or blessings referencing food written on the first few pages (such as, “be present at our table, Lord” or the popular Moravian prayer adapted from a traditional Lutheran prayer, “Come, Lord, Jesus, our Guest to be, And bless these gifts bestowed by Thee”). Though it may not seem like it at first, these similar formulas show a fair amount about these churches and their history.

Though none of the books explicitly explains why the churches are selling or distributing books (one can assume it is for fundraising or community building, typically,) one can still see that these churches find it important, if not necessary, to engage in the long tradition of making and disseminating church cookbooks. Further, though it would be easy to contact a publishing house and purchase a generic, customizable cookbook with recipes and housekeeping tips in it (there are two in this collection that seem to have done that) most of the time, the people of these churches choose to create the cookbooks themselves. They ask parishioners and community members for recipe contributions and in the end, though sometimes they aren’t the prettiest or most professional looking books, they are really the most fascinating and representative of their various communities. In their whimsical illustrations, humorous titles, handwritten marginalia, and funky recipe names (such as Ham Baked in Milk, Chili Cheese Festivity, and ‘Nut Nut’ Pie, to name a few) I believe we can find very authentic reflections of these communities, as well as the time periods in which they were published.

Though commentary on faith, fellowship, and food are typically to be expected when examining church cookbooks, there was one more aspect that really struck me in my work with these books, and that was the role of women. As a woman living in 2021, I don’t associate women with housework or with cooking; I see that as a more antiquated, more conservative idea. In working with these books, I was definitely expecting to see these outdated ideas about female identity at the forefront, obvious and transparent, and in some cases, I did. Surprisingly, however, I most often saw women using their roles as homemakers and cooks as moments of autonomy and power, rather than as submissive objects under the thumb of a father, husband, or other person. Unsurprisingly, a majority of the church cookbooks were made by women, be them women in cookbook committees or in women’s fellowship groups at the church. Further, the women who made these books and/or contributed recipes oftentimes seem, in the texts at least, to be aware of their roles and how they may be viewed by society.

A favorite book of mine from the collection is a prime example of this. The cookbook, Moravian Ministers’ Wives’ Favorite Recipes with Devotional Gems (1973), from Immanuel Moravian Church in Winston-Salem, is specifically by and about women’s’ experiences, and there are many moments throughout the book where the ladies seem to be commenting, tongue-in-cheek, on their roles in the household, the church, and the community. One of the first examples of this comes from the president of the women’s fellowship of the church, Mrs. Eugene F. Grace, who, after thanking those who contributed to the book, inserts a humorous quote: “An ungrateful man is like a squirrel under a tree eating acorns, but never looking up to see where they come from” (p. 000b). Though one could argue this is just supposed to be a witty moment, one could also argue that this moment serves as a nod to the importance of women within the hierarchy of the church, as they are the ones often expected to and entrusted with the duty to provide sustenance and succor to the men in their lives. It’s also interesting to note that the cover of this book has been altered slightly by someone with a pen, who changes the name to Ministers’ Wives’+ Husbands’ Favorite Recipes. Though we could sit and consider forever who altered the title and why they felt compelled to insert “husbands” into this book by and about wives, I think it’s more important to note that the change was made and make of it what we will.

In one of the many food-centric parables of the Bible, Jesus vouches for his disciples to the Pharisees, who are shocked to see them picking grain as they walk in a field on the Sabbath. Jesus reminds them of how the old rules of their religion were broken even by the most pious of men (David) and tells them plainly: “The Sabbath was made to meet the needs of people, and not people to meet the requirements of the Sabbath” (Mark 2:27-28, NLT). That is what I believe these cookbooks show us today. Jesus recognized and preached about the needs of the people being more important than adhering to ritual or tradition, and these books, though they may seem small in the grand scheme of things, continue to teach that message. These cookbooks are not only about community, but they are, most importantly, reflections of fellowship regardless of religion or creed—about faith in one another, as well as in our respective gods and beliefs. The recipes in these books, be them new (in their time period) or passed down through generations, signal how we, as humans, grapple with not only our needs and desires for food, but also how we shape ourselves and our identities around our spiritual beliefs. In the words of author and Episcopal priest Douglas E. Neel, “studies of the mundane topic of food help [us] to understand Jesus’ spiritual teachings: his parables about food and farming, the social and economic climate of the times, the stresses people faced as they sought answers in Jesus.”

References

Holy Bible: New Living Translation. (2004). Tyndale House Publishers, Inc.

Neel, D., & Pugh, J. (2013). The Food and Feasts of Jesus: The Original Mediterranean Diet, with Menus and Recipes (Religion in the Modern World). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Further Reading

Blakemore, E. (2017). What Amateur Cookbooks Reveal About History. JSTOR Daily. https://daily.jstor.org/what-amateur-cookbooks-reveal-about-history/

Church Cookbooks Offer a Taste of Methodist History. (2019). United Methodist Church Online. https://www.umc.org/en/content/church-cookbooks-offer-a-taste-of-methodist-history

Ferguson, K. (2020). Cookbook Politics. University of Pennsylvania Press. https://uncg.on.worldcat.org/oclc/1154615360